This past week, in Kyiv, Ukraine, I had the opportunity to walk through two quite incredible exhibits at the National Art Museum of Ukraine, with deputy director Yuliya Vaganova. I'll combine the two into this one post but both deserve deep attention on their own.

Heroes: An Inventory is a project that began several years ago, supported by the Goethe Institute of Germany, with the curatorial staff at the museum working with German curator Michael Fehr. The project began in the simplest of ways: the staff took an inventory, in every department, of every piece of art that was classified as "hero." More than 650 works had some identification as “hero”, “saint”, “martyr”, or “heroic deeds." 180 of those works were selected for the exhibition. Although this project was begun before the Maidan protests began; the revolution, annexation of Crimea and the war in the East, have made heroes a topic of significant conversation again. The exhibition's thoughtful text labels (hooray, in English as well!) encourage that conversation. In part, the introductory label says,

For us, therefore, this exhibition is much more than a self-reflection; it is an experiment which results will have a significant impact on the reorganization of the permanent collection and also might push the community to reflection.

The exhibit begins with a gigantic, non-removable marble statue of Lenin, hidden behind a wall for the decades since independence. Organized in a number of different categories, from heroes of labor to a room full of Stalin and Lenin (displayed as in a storehouse, in the top picture); to heroes of war; traditional Ukrainian heroes like Cossack Mamai; cultural heroes (the smallest group represented in the collection, Yuliya told me); religious heroes or saints; of course, poet and writing Taras Shevchenko. Each gallery included an interpretive text panel as well as an enlarged quote on the topic. The exhibition ends in a three-part way. The first is the most recent portrait of a hero in the collection: a Chernobyl liquidator. Then, a room that's used for programs and conversations--diving deeper into both scholarly and emotional aspects of heroism, and finally, a small wall featuring individual stories of personal heroes (and not surprisingly, moms and dads are important.)

Yuliya shared several important points about the exhibition development process that I think hold lessons for us all. First, that this was really a collaborative process, working across all the disciplines and collections of the museum, from ancient art to today. Second, that the collaboration with Michael Fehr was, as she said, the first international project that was not a colonial one, but really a partnership. Third, in comparison to the way most people visit museums in Ukraine, these were galleries of conversation. Everyone was talking to their family or friends as they went through the exhibit. And lastly, that the director of museum education said that it was the first exhibition that the museum had done that really didn't need an excursion with an expert to understand. That visitors, all visitor, could make their own meaning from the creative, thoughtful text, object selection and installation.

The second exhibition, Spetsfond, curated by Yuliya Lytvynets is a fascinating look at our own profession, within the context of the Soviet Union. To quote the museum,

In the National Art Museum of Ukraine (then the State Ukrainian Museum) Special secret storage was formed in 1937-1939. It contained works from Kharkiv, Odesa, Kyiv, Poltava and from special storages of Ukrainian art exhibition created by so called enemies of the people. They were formalists, nationalists, those who, according to party ideologists, "distorted reality" and threatened the existence of the "new society". Most of the names and artworks were forgotten for a long time in the history of Ukrainian art. Thus, the works of Oleksandra Ekster, Oleksandr Bohomazov, Davyd Burliuk, Viktor Palmov, Oleksa Hryshchenko, Onufrii Biziukov, Neonila Hrytsenko, Semen Yoffe, and lots of others were transferred to the Special storage of the NAMU.

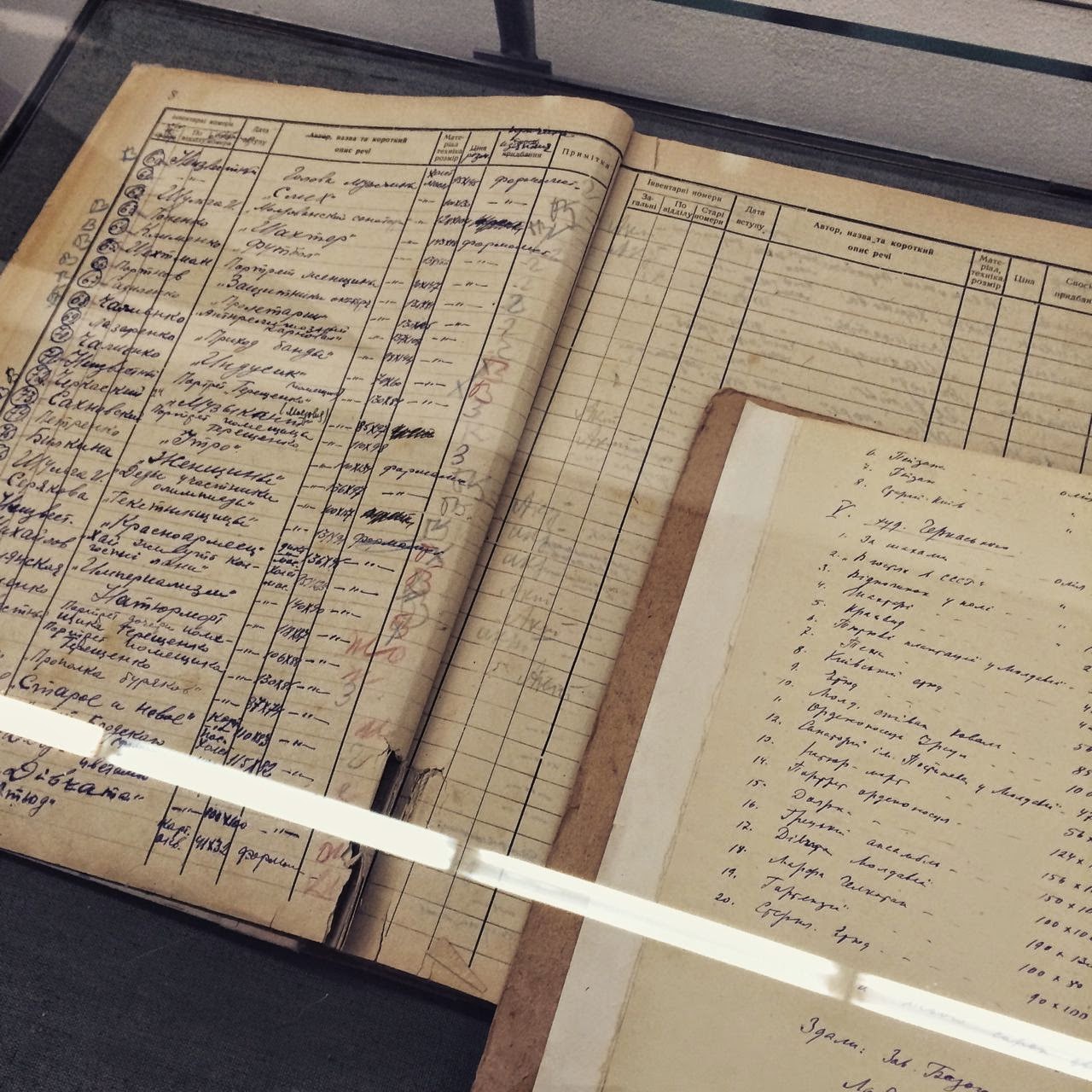

This special storage was open only to the director and the KGB. The works were removed from their frames and rolled away. The exhibition includes not only the works (some of which are head-shakingly normal) but also the records. Because after all, we are recordkeepers. A collections book noted the works that were to be stored away; it sometimes noted the fate of their creators ("artist arrested"). Also in the exhibit are some of the paperwork about the "trials" of the artists and the "reasons" for the works censorship. Interestingly, at one point, a passionate and courageous staff hit upon a solution of classifying the works with a prefix of 0, denoting that the works had no significant artistic merit--which then meant that nobody bothered to look at them to decide if they should be destroyed. And so they survived.

During my time in Ukraine these last weeks, I had many conversations with my colleagues about the new de-communisation laws passed by the Parliament. The laws are so vague as to be unclear about the impact on museums but they do ban Nazi and Communist symbols and, as I understand, define new heroes for Ukraine's history. As I walked through both exhibits I was incredibly moved and heartened by a museum who, though literally on the frontline of the Revolution last year, continues to build new ways of thinking about the past. History museums could--and should--take a lesson from this art museum's work.

Fundamentally, I realized that these exhibits are both about power. On the one hand, they both share the horrible power seized and exercised by the Soviet state; a legacy that continues to shape this entire region. But on the other hand, I see other, more hopeful uses of power here as well:

- the power of collaboration

- the power of storytelling

- the power of visitors, making their own choices and having their own conversations

- the power of documentation

- the power of objects

- the power of museum staff

- and most importantly, the power of museums to be centers of civic engagement.