Today's guest post is by Caren Ponty, a former student of mine in the Johns Hopkins University Museum Studies Program. She brings a wealth of experience from her career in community development, a perspective that inform her reflections on several efforts, on both sides of the Atlantic, to re-contextualize museum collections.

With the opening of the new Smithsonian African-American Museum on the Washington Mall last month and the AAM’s focus at the 2017 annual convention on diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion, I have been thinking more about what this means to museums, its audiences and its collections. Having worked on community equity issues as part of my career in community development, the one thing I think I know is that even the definition of diversity can be a tricky subject. The term can be applied to any number of areas that one considers outside the mainstream, whether it be race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, and more. No one seems to have a clear-cut characterization; it depends upon context, but it is based on representation.

This past summer while on a Johns Hopkins University graduate seminar in museum studies, I had two encounters with museum exhibitions which focused on seeking to redress the exclusion of blacks in collections in Great Britain. The first was at the National Portrait Gallery in London where the special exhibit Black Chronicles was a discrete intervention among multiple galleries throughout the museums. (For those unfamiliar with the term, art ‘intervention’ applies to art designed specifically to interact with an existing structure or situation, be it another artwork, the audience, an institution or in the public domain). The intention was to focus attention to the overlooked, underrepresented black community (which in Great Britain includes Asians) whose portraits would be few in a museum dedicated to paintings of the elite British. While the dispersed special exhibition seemed somewhat confusing, the photographs, particularly those hung in the first gallery on a stark black painted background. The portraits, from the 1850s through 1947s, showed unimaginable, stunningly-displayed images of private lives never seen. While snaking our way around to see the exhibit, I knew that it had made the impression intended when I spotted one of the exhibit portraits staring at me while at dinner at the Museum’s restaurant. I realized that prior to experiencing the intervention, I would have had no idea what the photograph was doing there and it may have seemed out of character. But aimed with this knowledge of interspersing the voices of blacks throughout the museum, it seemed to blend into the room in a way where it might seem naturally suited.

This same technique is being used at The Old Manse in Concord MA in a project entitled Art and the Landscape. (Note from Linda: Caren has been working with me on an unrelated interpretation project at this site). One element of Art and the Landscape, created by artist Sam Durant, added artifacts related to the African presence in Concord to the interior of this historic house. The goal, similar to the project at the National Portrait Gallery in London, is to make the struggles, history, and culture of Africans in Concord more visible within the historic narrative and to integrate the knowledge that enslaved people lived here and were part of the Reverend Emerson’s household at the time of the American Revolution. Visitors who have seen these interspersed objects or participated in some of the prototyping have walked away commenting that prior to seeing the exhibit, they never thought much about this issue. This is particularly interesting given that this is a community best known for fighting for their right to be represented in government. As few people visit for the tour that focuses exclusively on this aspect of history, one can see the value of the interventionist approach to reach more visitors and provide them to think more about this part of our national heritage.

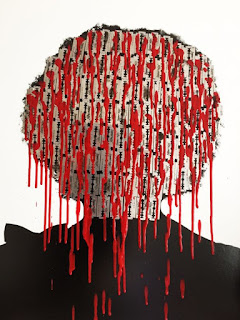

The second approach I saw to engage diversity was Raphael Albert’s Miss Black and Beautiful at Autograph ABP’s exhibits at their own galleries in Shoreditch, London. Curator Renée Mussai (who had also curated Black Chronicles mentioned above) has a remarkable and relatable display of black beauty pageants from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, including some from London, and spoke to us about the unanticipated interest from black women--close to 850 people showed up for the opening. But even more brilliantly, running simultaneously in their upstairs gallery was an exhibit entitled Unsterile Clinic, whose goal is to raise awareness of the widespread practice of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). As described on their website, Aida Silvestri’s sculptural photo-works are shown with text poems based on interviews conducted with participants whose personal testimonies provide harrowing insight into their experiences. This juxtaposition of social beauty and social justice was bone chilling.

Making visitors aware of an uncomfortable topic while sharing images of pride and more acceptable subjects brings me back to our new American museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Here, the events of our American heritage, which includes our African-American past that is part of all of us, are served by a museum that makes us proud by elevating the narrative of who we are in a broader and all-encompassing manner.

Images:

Sarah Davies (formerly Forbes Bonetta) and James Pinson Labulo Davies

by Camille Silvy, 1862

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Brochure, The Meeting House, Art in the Landscape

Aida Silvestri, Type II B: Distance. From Unsterile Clinic, 2016

by Camille Silvy, 1862

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Brochure, The Meeting House, Art in the Landscape

Aida Silvestri, Type II B: Distance. From Unsterile Clinic, 2016

No comments:

Post a Comment