Monday was World Refugee Day so it seems the past time to share one of the most meaningful museum experiences I’ve had in a long time. It’s taken me far too long to write about—but if you’ve been in conversation with me over the last several months, I’ve probably told you about it.

In April, my dear friend and colleague Katrin Hieke joined me for a weekend of museum-going in Berlin and she had scouted out exhibits that I never would have found. One of them was at the Museum of European Cultures—a museum I couldn’t quite imagine. What would it be about? High culture? Folk culture?

Here's how the museum explains its work:

The Museum Europäischer Kulturen is dedicated to collecting, researching, preserving, presenting, and raising awareness of artefacts of European everyday culture and human lived realities from the 18th century until today. As such, we transcend national and linguistic borders and facilitate encounters among different groups of people. Our work is characterised by the term ‘cultural contact’.

We continually seek to forge connections between our historical collection and current issues. An important aspect of this work is a close cooperation with respective interest groups, as well as facilitating an exchange with our visitors.

The staff, led by director Elisabeth Tietmeyer, have chosen to continually expand all of our perspectives on what “European culture” is. Katrin had found that they offered Tandem tours, in German and Arabic, of the exhibition "daHeim: Glances into Fugitive Lives" so we arrived just in time. What’s a Tandem tour? One of the refugees/artists who created the exhibit led the exhibition tour, joined by a museum curator and a translator. Along the way, our small group not only conversed in German and Arabic, but English and Greek.

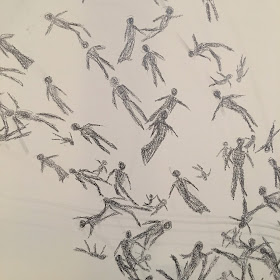

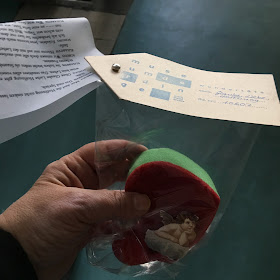

What was the exhibit? It was the work of a small group of refugees, from all over the world, who were housed at a single hostel in Berlin. Using the hostel bedframes as their primary material, they created extensive installations, along with art work on the walls and in smaller iterations, that explored their own experience as refugees coming to Berlin. The works were powerful in and of themselves, but our guided tour made it even more so. He Xshared the stories of creating the works and of individual refugee stories. The group of creators became a cohesive group, and now, even after the exhibit is finished, meet every week to socialize.

The works depicted the often-harrowing journey, the German bureaucracy, families left at home and memories of cities destroyed. And in every instance, our guide made the experience deeper, more personal, more real. At the small bedframe, adapted with rockers to simulate the rocking of a boat, with a small iPhone-sized video of someone’s voyage, when he shared his own journey, we all fell silent, suddenly into a world unknown to us. So as humans, the exhibition touched Katrin and me deeply. But there are also important lessons for us as museum people.

Here’s a few takeaways:

Here’s a few takeaways:

- Be fearless. This was a big exhibit with, I suspect, an unknown outcome when it began. The staff had to trust its exhibition partners, the refugees themselves, and its own ability to explain and explore the content.

- Let go of your “museum” voice. We talk a lot about shared authority, but then, often, we resort to exerting control after we talk to an “advisory committee” and get their input.

- Be about the now. More than ever, the world needs more thoughtful, passionate voices exploring how we can make a better world together. The long lead time for exhibition development often shoves us into irrelevancy.

- Don’t just talk. It’s pretty easy to talk about how museums should be relevant and how we should be more diverse. We are still moving way too slow and need to pair institutional and personal action. Last year at ICOM, the mayor of Lampedusa, Italy, where many refugees have come ashore, spoke about how history will judge all of us in receiving nations harshly for our lack of actions in the refugee crisis. We must do more.

Want to explore more about migration and cultural organizations? Check out the free downloadable publication, The Inclusion of Migrants and Refugees: The Role of Cultural Organisations coordinated by Maria Vlachou and just released this week.